US Army is open to returning Remains of American Indian Children buried in Carlisle

Buildings at the Carlisle War College that once were the Carlisle Indian School, March 22, 2016. James Robinson, PennLive.com

By Red Power Media, Staff | May 6, 2016

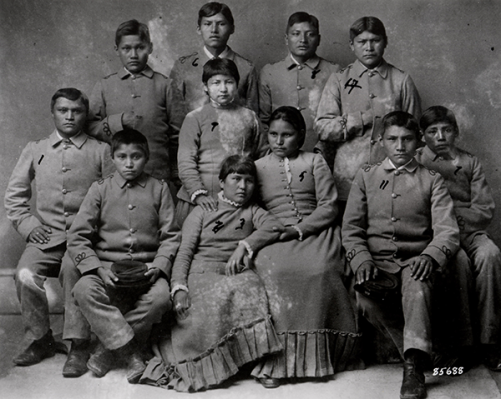

Nearly 200 American Indian children perished at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

For more than 100 years, American Indian children have been buried at Carlisle, the school that sought to cleanse their “savage nature” by erasing their names, language, customs, religions, and family ties.

Between 1879 and 1918, more than 10,000 American Indian children were housed at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the federal government’s flagship boarding school based on a strict military model.

The children were stripped of all tribal traditions. Their native names were changed to European names and they were forced to adopt the traditions of white America.

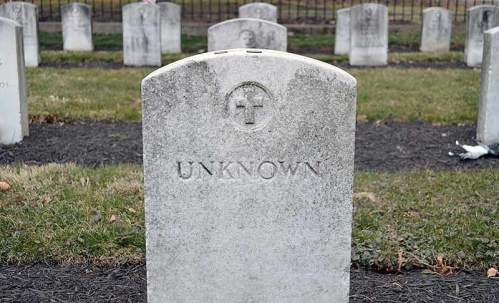

Nearly 200 of the children perished at the school, most from diseases like tuberculosis or consumption. Their remains were never returned to their families. The children’s final resting place is on the grounds of what used to be the boarding school and is now part of the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle.

Grave-sites at Carlisle cemetery are often decorated by visitors with small stuffed animals, dreamcatchers and toys.

Now there’s a chance that some will be sent home to their tribes.

Patrick Hallinan, the head of Army cemeteries said in an interview that he’s open to meeting American Indian demands to repatriate children’s remains, provided talks on the matter prove fruitful and all regulations are met.

This marks a reversal for the Army, which in winter denied a Rosebud Sioux request to return 10 tribal children to South Dakota.

Now the Army confirms it will send two officials to Rosebud on May 10, to begin formal government-to-government consultations with the Sioux, the Northern Arapaho of Wyoming, and a third tribe that now seeks the return of its people, the Northern Cheyenne of Montana.

“I think things are going to happen,” said Russell Eagle Bear, the Rosebud historic-preservation officer. “I’m hoping they’re going to tell us they’re ready to work with us and let our relatives go.”

If that occurs, he said, an intended summer tribal pilgrimage to Carlisle could become an advance party to plan the return of Sioux remains.

The nearly 200 children that lie in the Carlisle cemetery were among thousands taken from native families in the West, spirited a thousand miles to the East, and forced through a wrenching experiment in assimilation.

Today many American Indians view what took place at Carlisle as genocide.

Hallinan says, the decision to return remains from Carlisle to Rosebud or elsewhere, rests with him.

“If the tribes are interested and this is something they want to do, we would be supportive to see that accomplished,” Hallinan said. “We look forward to working with the tribes, and we think that once we sit down and consult with them, there should be a positive outcome for all involved.”

He plans to send staff to two American Indian conferences this year, to see if other tribes wish to discuss the status of their ancestors’ remains.

While the Army plans to send two people on May 10, dozens could attend from Indian nations. Leaders of the Rosebud Sioux, Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne River Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, Standing Rock Sioux and Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribes will meet on Tuesday, in Rosebud, South Dakota with representatives from the federal government and the U.S. Army to begin negotiations over the repatriation of the children’s remains.

All six tribes intend to have people there, and the Rosebud Sioux will bring lawyers, political leaders, and tribal staff. South Dakota’s senators and congresswoman will send representatives.

This month’s meeting in Rosebud could portend a major step forward on an issue that torments many native peoples. It comes amid an outpouring of interest and awareness that followed a March 20 story in the Inquirer.

Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first federal Indian boarding school, spawning a fleet of successors that embraced the motto, “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

At Carlisle, children who spoke their native language could be beaten, while overcrowding and malnourishment weakened students, making them vulnerable to epidemics that swept the school.

Today many Indian researchers and activists refer to those who attended Carlisle and similar institutions as “boarding school survivors.” They say collective trauma and grief contributes to the devastating social ills that plague tribal communities.

Officially the Carlisle cemetery contains 186 graves. Thirteen are marked “Unknown.” Many of the headstones bear names but no birth or death dates.

For approximately three decades beginning in the latter part of the 19th century, the federal government, in an effort to “tame the savage” and assimilate them into the dominant white culture, uprooted close to a million American Indian children from their reservation tribal homes, transporting them thousands of miles across the country to boarding schools.