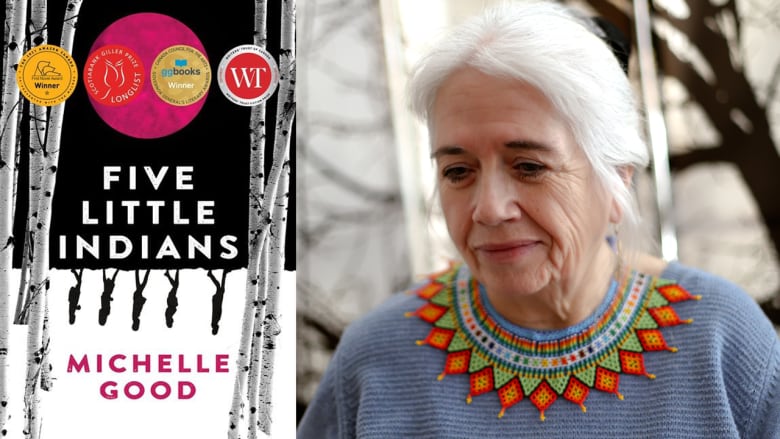

Christian Allaire is defending Five Little Indians by Michelle Good on Canada Reads 2022

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

Michelle Good is a writer, retired lawyer and a member of Red Pheasant Cree Nation in Saskatchewan. Her poems, short stories and essays have been published in magazines and anthologies across Canada.

Good's debut novel Five Little Indians is a bestselling book that chronicles the quest of five residential school survivors — Kenny, Lucy, Clara, Howie and Maisie — to come to terms with their past and find a way forward. Released after years of detention, the five teens find their way to the seedy and foreign world of Downtown Eastside Vancouver, where they cling together, striving to find a place of safety and belonging in a world that doesn't want them.

Five Little Indians won the 2021 Amazon Canada First Novel Award and the 2020 Governor General's Literary Award for fiction. The novel has also been optioned by Prospero Pictures to be adapted to screen as a limited TV series.

Five Little Indians will be championed by the journalist and author Christian Allaire on Canada Reads 2022.

Canada Reads will take place March 28-31. The debates will be hosted by Ali Hassan and will be broadcast on CBC Radio One, CBC TV, CBC Gem and on CBC Books.

In May 2021, the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in B.C., uncovered the remains of 215 children on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

The news has had an emotional effect on Good, who is currently based in southern British Columbia. She spoke with Shelagh Rogers about why she wrote Five Little Indians — and why the legacy of Canada's residential school system stays with her.

Calls to action

"That first weekend after the Kamloops announcement was really rough. I told a friend of mine that I felt catatonic after that announcement. It's not because we didn't know. We did know. People have been talking about this for years and years. But there's never been any support to resolve this, to do what the band has done themselves.

"But the thing that really, really bothers me — and it actually infuriates me and I try to stay away from being infuriated — is in 2015, when the Truth and Reconciliation report was issued, there are six calls to action, 71 through 76, that are up here under the heading of 'missing children and burial information.'

"Murray Sinclair and the other commissioners basically gave the federal government a roadmap for how to address this issue through those calls to action. They developed a budget to go with it. And the federal government said no.

I would bet you my bottom dollar, you're going to find one of these grave sites virtually at every residential school.

"So when I hear the prime minister speaking about how 'all children matter' and flying the flags at half mast, it's a lovely symbolic gesture. But it does nothing. What they need to be doing is providing the resources, the expertise and the support.

"They need to protect these lands. I would bet you my bottom dollar, you're going to find these grave sites at virtually every residential school."

The half-life of trauma

"There was a reason that I chose to pick up the story upon the release of the characters, whether it's escape or when they age out or whatever. Through all of the work that's been done in the form of memoir, in the form of the Truth and Reconciliation report, I think that there is some understanding of the nature of the abuse that children suffered.

"What was missing was how that trauma has a half-life that continues for generation upon generation upon generation. When people ask that question, 'Why can't they just get over it?' I've started to transpose that into another question, which is, 'What is it that they're asking us to forget and get over?'

We simply cannot forget 120 years of colonial brutality.

"It was 120 years of taking every school-aged child from our community — from their parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings. Are they asking us to forget that? And how could we?

'It's had such an impact on the integrity of our cultural cohesion, which was the intent. So, no, we simply cannot forget 120 years of colonial brutality."

Creating community

"I went to the MFA program at UBC to write this book — but I had no idea what I was doing or what it was going to look like. It started with Kenny; it started with me writing about those first pages with that character.

One of the impacts of this kind of abuse...is a real struggle to maintain meaningful relationships in your life.

"I immediately realized that I needed more characters because to be able to express the scope, the range of injury that was suffered by kids, I needed more than one person. There were so many forms of abuse: abuse that was specific to young girls, and abuse that was specific to young boys.

"One of the impacts is a real struggle to maintain meaningful relationships in your life. So that was another thing that I wanted to demonstrate through the relationships between the characters. But the other thing is that when you have five characters, you have a community. And that's what these kids were to each other.

"They created a community for each other."

What stays with me

"The characters from the novel have been in my life for many years. They came to feel like my kids, as though they were my children. I still find myself reaching for them in my mind.

"Many, many survivors have reached out to me and given me some very strong and supportive feedback. They've told me that they could see themselves in these stories and that they were grateful to have these stories out in the world — for the same purpose that I have in putting them out in the world.

The characters from the novel have been in my life for many years...I still find myself reaching for them in my mind."That, more than anything, is really, really satisfying."

Support is available to anyone affected by their experience at residential schools and to those who are triggered by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support to former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment.