How Manifest Destiny Stretched the U.S. From Sea to Shining Sea

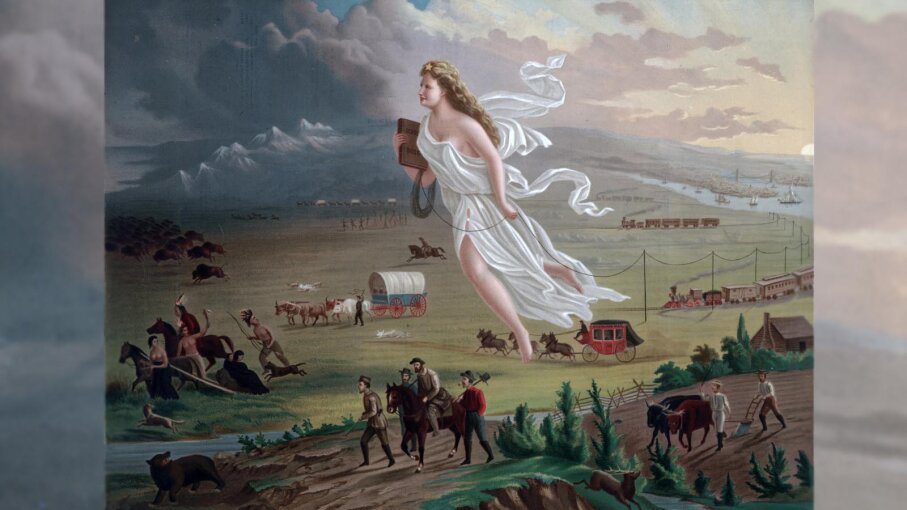

Of course, there's more to Manifest Destiny than some woman in white or the encouraging hand of the Almighty. The concept was inextricably tied into the politics of the time, which were (as now) fueled by something decidedly unholy: money.What Lies Behind the Woman in White

America's land-lust was driven, first and foremost, by the thirst for more wealth for its settlers. But distributing that often ill-gained bounty was not easy. In a time when the scourge of slavery already was beginning to rip apart the nation, the issue of how to divide the newly acquired land — which states-to-be would allow slavery, and which would not — became a political hot potato.Declaring the land grabs a divine right seemed, if nothing else, a nice cover story for expansionists of the time. But even more than money, politics or religion, Manifest Destiny demonstrated something else about the mindset of many Americans.

"Implied in the notion of Manifest Destiny is that we know best," says Don Haider-Markel, the head of the department of political science at the University of Kansas. "And basically, when we say 'we,' we mean sort of Anglo-Saxon Protestant, otherwise known as sort of white.

"That's telling Native Americans, that's telling Mexicans, that's telling Africans we kidnapped and used as slaves that we are superior. Our way is superior.

"I don't see how you can escape from the notion," Haider-Markel says, "that this is a form of white supremacy."

|

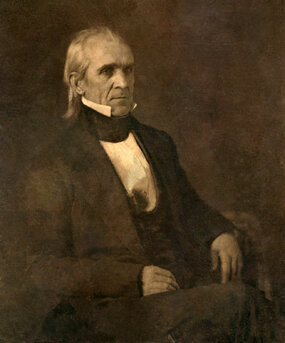

President James Polk was a champion of Manifest Destiny and built his presidential campaign around the idea. Public domain |

Did People Really Accept the Idea?

Certainly, many people at the time believed in Manifest Destiny; that God wanted the newcomers to take over the continent, to work the land, to bring Christianity to the Indians and Mexicans, to be Biblically fruitful and multiply (as O'Sullivan put it), and, if God found it within His grace, to grow rich while doing it. Expelling more than 100,000 Native Americans from their homes in the American South, murdering thousands of others, and taking land from Mexicans was not simply accepted as a divine American right to these people. It was a duty.But not everyone bought into that notion. Not by a long shot. Many saw the idea as little more than a dodge.

"There were people, for example, who thought that the drive to annex Texas was a ploy to gain more land to create more slave states, because eastern Texas was suitable for growing cotton," says Harry Watson, a professor of Southern culture at the University of North Carolina. "Even then, there were people who were bitterly opposed to slavery and desperately wanted to abolish it, and the first step to abolishing it might be to prevent it from growing. They did not want to admit Texas, they did not want to fight Mexico to get Texas, they did not want slavery to be allowed to spread. All of this was fought out very bitterly in Congress."

Still, politicians like President James K. Polk found it politically and economically favorable to press onward. His call to annex both Texas and Oregon (which would appeal to both Northern and Southern states) helped win him the presidency in 1845 over anti-expansionist Henry Clay, even though Polk's drive threatened war with both Great Britain and Mexico.

By the time Polk left office in 1849, Manifest Destiny was all but complete. America, barely 60 years after the U.S. Constitution was ratified, now stretched from sea to shining sea.

Keep reading

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment.