That's according to Melissa Olson, a legal advocate for Native children.

"This was not an accident of history, it was a government program designed to save the government money and dismantle tribes. All under the guise of integrating Native children more fully into American society," Olson said in a documentary she produced exploring the cultural and historical impacts of forced adoption, titled "Stolen Childhoods."

When the BIA started the project it enlisted social workers to visit reservations and convince parents to sign away their parental rights. It was a way to assimilate these children into "civilization," Olson said. The government believed adoption was the best option for dealing with the Native children "problem."

"When you removed a child and put them in a non-Indian family, they wouldn't be getting to know other Indian people as they would in a boarding school, they would hopefully be raised in a middle-class family. And so the idea was that they would be fully assimilated, and at no cost to the government," said Margaret Jacobs, author of "A Generation Removed," a book on forced adoption.

The adoption project sold their idea to white families using advertisements asserting that to not adopt would be choosing to leave children with no chance of survival — as in their own families would not be able to provide and care for them so it was up to these white families to help, Jacobs said.

By the 1960s about one in four Native children were living apart from their families. During this era, social workers found more dubious ways of taking children from their mothers.

"One of the things I found that really shocked me was a form that the Bureau of Indian Affairs developed. It was called 'authorization for discharge of an infant,' something like to a person who's not a family member. So it doesn't say authorization to adopt, or anything like that. It says nothing about losing one's child, or giving up rights to one's child, or putting a child up for adoption," Jacobs said. "It's all this sort of legalistic language that I didn't understand either when I was reading it."

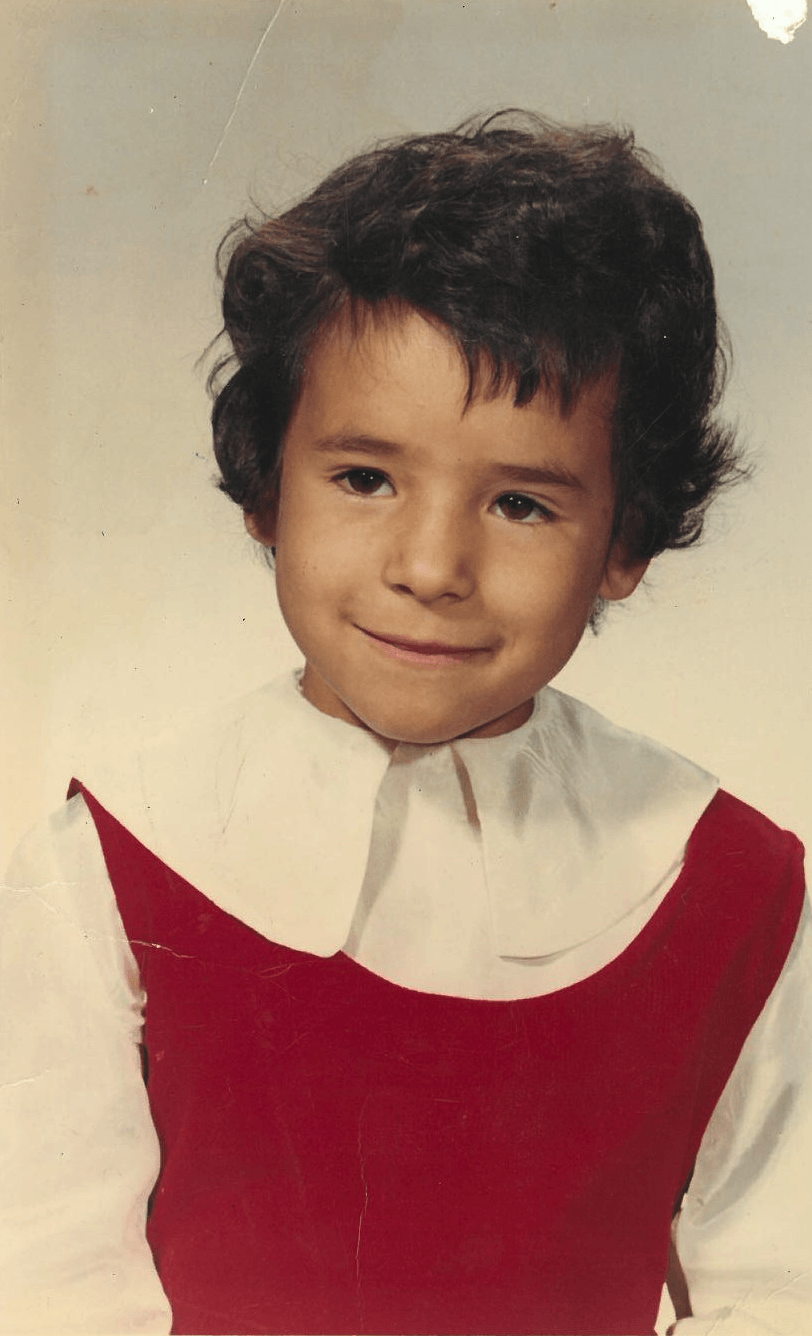

Many of these adopted children, now adults, struggle with memories from traumatic childhoods in abusive homes, while trying to figure out where they fit in as Natives in white communities. Olson followed a few of these people's stories in "Stolen Childhoods."

The documentary was produced at KFAI by Melissa Olson and Ryan Katz and edited by Todd Melby.

To listen to the documentary, click the link above.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment.