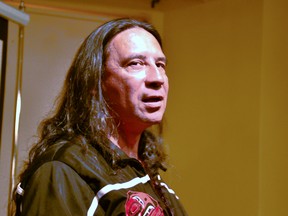

Christin Dennis shared his story in the lead up to Canada's National Truth and Reconciliation Day

At just six years old, Christin Dennis was taken from his home on Walpole Island.

He was forcibly rehomed with a white family as part of the Sixties Scoop, a nationwide mass removal that took Indigenous children from their families and placed them into the child welfare system, often without family or band consent.

Following a screening of the National Film Board of Canada documentary Birth of a Family Wednesday night at the Falstaff Family Centre in Stratford, Dennis shared details of his personal journey that took him away from a happy, healthy home and exposed him to years of physical and emotional abuse, isolation, addiction, crime, and a debilitating post-traumatic stress disorder before he found a way to reconnect with his culture and his people, and began to heal.

“When this gentleman (from the Children’s Aid Society) had my suitcase, I remembered thinking, ‘There’s something not right here,’ ” Dennis recounted. “He says, ‘You’re going for a car ride,’ and I’m thinking, ‘I don’t want to leave.’ I really enjoyed being where I was. Sure enough, I start screaming, ‘I’m not getting in that car.’ … It’s interesting. You can actually manipulate children quite easily. They could be in a mood and you give them some candy … and it changes. I remember the Children’s Aid Society guy … was there to pick me up to go see somebody to be adopted. He says, ‘I’ll let you drive my car,’ and I thought that was the coolest thing.”

Dennis said he was taken to live with his adoptive family and, while his new life didn’t seem too bad at first and there were some good times growing up with his new siblings, he was forced to cut his long hair and quickly learn to speak proper English or incur the wrath of his adoptive father, a local minister. As a young child, Dennis said there were numerous instances when he was beaten so badly by his father that he wanted to die, leaving him with severe PTSD that would manifest itself with severe shaking and even seizures when he became stressed or scared.

The trauma didn’t stop when he went to school. Once the family moved to Wellington County, he was constantly bullied for being one of very few – if not the only – Indigenous student in class.

“I learned to hate my culture,” Dennis said. “I learned to be white as much as possible. I learned to speak English. I learned the Bible. I read the Bible. I remember I found alcohol, too, at the age of 11. Alcohol was kind of interesting. It actually made me feel good. I spent most of my life in fear. That six-year-old was gone. From seven years old and on, I was just living in that survival mode.”

His discovery of the numbing effects of alcohol began a cycle of addiction and non-violent crime that landed him in a Guelph prison for the first time just before his 16th birthday. For almost the ensuing decade, Dennis said he was in and out of prison, unable to hold down a job when he was out, and ultimately began selling marijuana to pay for his addiction.

But that time in prison was a turning point. He said he met more Indigenous people on the inside in school or in the community. While in prison, Dennis found religion and became a born-again Christian, but still hated his own culture. It wasn’t until a prison chaplain convinced Dennis to experience a sweat lodge offered through the Native Sons program at the Guelph Correctional Centre – a program led by Indigenous counsellors and elders to reconnect Indigenous inmates with their cultures — that he started to come to terms with who he was.

“You could feel the intensity of the heat and it’s like, ‘What the heck,’ and then the (sweat lodge conductor) closes the door,”said Dennis, who also goes by Gzhiiquot or Fast Moving Cloud and is originally from Aamjiwnaang (Chippewas of Sarnia First Nation). “Next I know, he starts praying in a language and he’s throwing cedar tea and lavender tea onto these (red-hot rocks), and every now and then, I’d see sparks flying off the rocks like it was the universe upside down.

“I realized there’s something really powerful here. I was so humbled in that moment, I actually realized God is here and I realized God is everywhere. I think that’s what the (chaplain) wanted me to realize. You don’t need to be something that you’re not in order to be who you are.”

Though Dennis continued to struggle with his addictions, he found that conducting his own sweat lodges, something he now offers for others, helped him keep those addictions in check. Later in life, Dennis said he also found relief from his PTSD through the use of ayahuasca, a traditional South American hallucinogenic medicine.

In prison, Dennis also discovered a love for art but realize he needed to learn more about his own culture to find his voice as an artist. He studied and experienced traditions from many different Indigenous cultures and reconnected with both his biological mother and the Aamjiwnaang community.

“I got to meet (my mom) for the first time and I remember it was one of the most scary moments in my life,” Dennis said. “The whole time when I was adopted, I had always hoped that my real parents would come and get me and say, ‘We love you. We’re sorry that this happened.’ And they would embrace me. That never happened. So I go to meet my mom for the first time as a young man … and it was probably the most awkward moment of my life.

“I remember she had scars on her arms on both sides … and that scared the life out of me. I’d heard about people slashing their arms all the time. That’s what she did as a young woman. She used to cut herself,” Dennis added. “My mom is a day school survivor and her mom is a residential school survivor. I didn’t know how to deal with that and I started drinking again, and we didn’t have contact for probably 10 years after that.”

Equipped with a new sense of self and purpose, Dennis embraced his passion for art, majoring in fine art at Georgian College in Owen Sound and later learning photography through an apprenticeship under acclaimed Canadian photographer Michael McLuhan, son of renowned Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan.

“An art dealer found my art and, lo and behold, it got such recognition that the Longyear Museum of Anthropology got the art in New York and it’s a permanent collection,” Dennis said. “That was the stepping stone for my art. … I was in demand. My art is also in the permanent collection at Lac La Biche at the Aboriginal Peoples Gallery and my work hangs with some of the most prestigious Indigenous artists in Canada.”

For Dennis, truth and reconciliation is about sharing stories like his in the interest of helping Indigenous and non-Indigenous people come to a common understanding of atrocities like the Sixties Scoop and the residential school system.

“The truth is the truth and it sucks, but we need to come to place of understanding each other and sharing,” he said.

To that end, Dennis is working with the Falstaff Family Centre to host a number of events and activities this week, culminating on National Truth and Reconciliation Day this SEPTEMBER 29.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment.