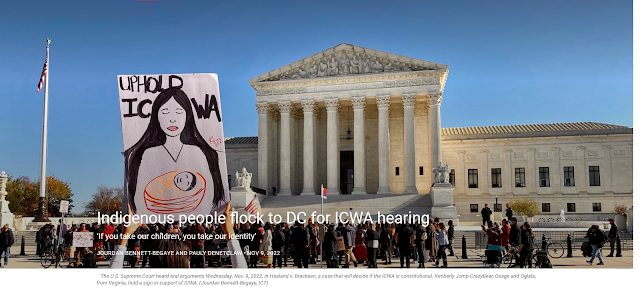

NOVEMBER 5, 2022 THE HILL

Supreme Court’s ‘sleeper’ case is major clash over Native American adoptions

The Supreme Court heard a dispute over a

longstanding federal law that gives preference to Native American

families and tribes over non-Native couples when deciding where to place

Native children in custody proceedings.

Although overshadowed by the court’s more politically charged cases,

legal experts say the dispute could prove hugely consequential for

Native American rights and tribal sovereignty.

“It is a sleeper case,” said Mary Kathryn Nagle, a Native rights attorney who filed an amicus brief in the case. “For Indian country, it is maybe one of the most important cases that has ever gone before the Supreme Court.”

The dispute tees up questions about whether the Indian Child Welfare

Act (ICWA) unlawfully imposes race-based preferences when placing Native

children, and if the law amounts to excessive federal overreach into

state adoption policy.

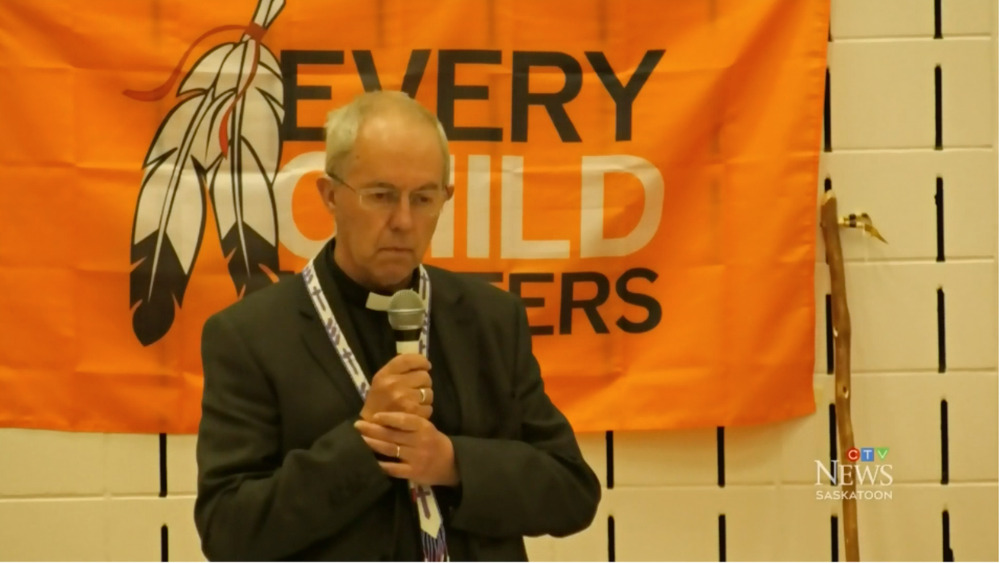

The case plays out against the uniquely troubling history of

mistreatment suffered by the country’s Indigenous population, including

the once-common practice of separating Native American children from

their families and tribes, which the ICWA was designed to combat.

The Supreme Court looked very different when it last confronted a major ICWA question in

2013 and counted the late Justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader

Ginsburg among its members. Although the court now has a solid 6-3

conservative majority, some court watchers believe the current ICWA case

could produce a split among the court’s conservatives.

The complex dispute to be heard Wednesday began when three white

couples who sought to adopt Indian children sued the federal government

over ICWA. Later, additional plaintiffs including the state of Texas

joined the case, and several Indian tribes intervened to support ICWA.

Texas and the other challengers claim, among other things, that the

law’s provision giving preference to Native American adoptive parents

over non-Native parents violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th

Amendment.

“A classic example of so-called ‘benign’ discrimination, ICWA creates

a government-imposed and government-funded discriminatory regime

sorting children, their biological parents, and potential non-Indian

adoptive parents based on race and ancestry,” Texas wrote in court

papers.

“Because this Court has recognized that ‘the way to stop

discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the

basis of race,’ such methods violate equal protection.”

ICWA’s passage arose in response to the frequent separation of Native

children from their families and communities by state child welfare and

private adoption agencies.

According to research conducted around the time

of ICWA’s passage in 1978, around 25 to 35 percent of all Native

children were removed from their families and placed either into foster

homes or with adoptive families or other institutions. Among Indian

children in foster care, roughly 85 percent were in non-Native homes,

according to a 1969 survey of 16 states.

“This law was passed against a very disturbing and tragic history of

the wholesale removal of Indian children from families to assimilate

them into white culture based on prejudice about Indian culture,” said

frequent Supreme Court litigator Lisa Blatt at a recent legal forum.

Blatt argued the 2013 ICWA case on behalf of a non-Native adoptive

couple.

“It started with the Bureau of Indian Affairs putting all these kids

in horrendous boarding schools, and then it then transitioned to the

‘60s and ‘70s to state custody removal proceedings,” said Blatt, a

partner at the law firm Williams & Connolly.

In practice, ICWA requires that Indian children be placed with

members of their extended family or tribe, or other Native American

families before outside candidates may be considered.

Ben Kappelman, a partner at the law firm Dorsey & Whitney who has

provided pro bono services to a Minnesota Indian tribe in child welfare

proceedings, touted the law as a success.

“ICWA, considered the gold standard in child welfare policy,

establishes priority for caregivers of Native American children whose

parents cannot care for them,” he said.

Supporters of the law say the ugly history that led up to its

enactment underscores the enduring need for protections for Indian

children and families’ culture.

“ICWA is based on a simple idea: When Indian children can stay with

their families and communities, Tribes and children alike are better

off,” the tribes wrote in court papers. “By implementing that simple

idea, ICWA ‘promotes the stability and security of Indian tribes and

families’ and ‘protects the best interests of Indian children.’”

The Justice Department, on behalf of the Biden administration, is arguing in support of ICWA.

The case has the potential to create a split among the court’s

conservatives, some experts say. Blatt, of the firm Williams &

Connolly, noted that Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, has

“consistently ruled” in favor of tribal rights and law.

“I think the assumption is that the United States that’s defending

the law with the support of the tribes, has at least four votes,

assuming they have Gorsuch’s vote,” she said. “And that leaves the

challengers needing to pick up both Justice [Brett] Kavanaugh and

Justice [Amy Coney] Barrett.”

A decision in the cases, Haaland v. Brackeen, is expected by summer 2023.

👇👇👇

When You Take Away the Kids, You Take Away the Future

The case that seeks to strike down the Indian Child Welfare Act is about colonialism, not civil rights.

LISTEN:

%20on%20Twitter.png)