Heartbreak and hope - The Vietnamese children of Operation Babylift and their battle to find birth parents and their identity

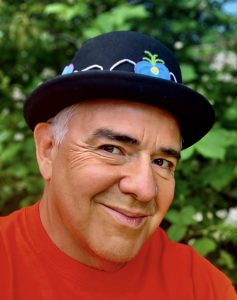

Andy Yearley still vividly remembers the journey he made from the Isle of Lewis to Vietnam 20 years ago. Travelling with a film crew from Mac TV in Stornoway, he had what he calls “the most unforgettable, vivid and surreal week of my entire life”.

Born in 1973, Yearley was one of thousands of young Vietnamese children evacuated from the country as the Vietnam war finally ended, culminating in a huge, US-led initiative in April 1975 called Operation Babylift. The children, many transported on military aircraft, were adopted by families in the USA, Australia and across Europe. Yearley’s Vietnamese name is Nguyen Tang; adopted by a Scottish couple, he grew up as Andy in a small, seaside village on Lewis, knowing virtually nothing about his biological family. The aim of that 2004 journey was to try and find them.

“A normal tourist visiting Vietnam finds stimulation overload, but in my case it was my first time seeing the country of my birth, potentially finding blood family, surrounded by a Gaelic TV crew, and escorted by a high up official from the Vietnamese government,” recalls Yearley. “Surreal was a total understatement.”

Yearley is a professional musician who has performed at Celtic Connections, HebCelt, and other high profile Scottish events, as well as teaching music to children. In Saigon, he remembers visiting a music shop where the shopkeeper talked at him for half an hour in Vietnamese. Not understanding a word, Yearley eventually decided to respond in Gaelic, just to see what would happen. “I said something along the lines of "Ciomair a tha thu? Tha mi duillich, a bheil Gaelic agad?" (how are you, sorry do you speak Gaelic?). The look on her face!”

Yearley never found any members of his Vietnamese family, but thanks to orphanage staff he was at least able to identify and visit the street where he had been found as a baby, next to a dead woman thought to have been his mother. “It was 5am and the street was buzzing with activity. To a lot of folk, their first known location is a hospital bed, or a birthing pool. Here I was at mine – a bustling, beautiful street with overgrown foliage everywhere, children, cats and dogs running wild, and a barely discernible old train track running through it. I quite like the fact that this last day was not filmed. It was a very personal moment.”

Two decades later, Yearley is one of the creators of Precious Cargo, a new theatre show coinciding with the 50th anniversary of Operation Babylift. Developed in Uig on the Isle of Lewis, Precious Cargo is now set for a full Edinburgh Fringe run at Summerhall following its debut performance at An Lanntair in Stornoway at the beginning of July.

The show grew out of a chance meeting in autumn 2021. Australian actor Barton Williams, also a Vietnam war orphan, was visiting Lewis as one of the cast of Silent Roar, a feature film about Hebridean surfers that was being shot in Uig and would ultimately go on to open the 2023 Edinburgh International Film Festival. Introduced by one of the film crew, Williams and Yearley made an immediate connection. Both had been raised by white families, growing up as virtually the only Asian child in small, overwhelmingly white communities, with no connection to their Vietnamese language or heritage. Both had later travelled back to Vietnam in the hope of finding their biological families but had returned home with no answers – a common experience for adoptees, so much information having been lost in the chaos of war.

Williams had been telling his own story for a while in various ways, in a children’s book, a short film, and in a solo stage show which he had developed as far as a work in progress performance at the Vaults in London. When he met Yearley, though, something clicked. “Andy understood the displacement I felt, looking Asian from the outside but something else inside,” he says. “He’s me, but Scottish.” Precious Cargo has now become international in scope, telling not just Williams’ story but those of five other adoptees living across the world, including Yearley, who also composed the musical score. All of the adoptees featured in the show grew up in very different places and circumstances, from rural Iowa to small town England, but with a powerful shared experience.

Operation Babylift may have saved many lives but it was controversial even in 1975. The first flight crashed a few minutes after take-off, killing 138 people including 78 Vietnamese children. Photographs from the time show rows and rows of babies being flown to their new Western homes in boxes. There were questions as to the USA’s motivation; to what extent was it a public relations exercise after an infamously disastrous war? In one of several eye-opening historical details, Playboy founder Hugh Hefner provided his private plane, the ‘Big Bunny’, to transport 41 Vietnamese orphans from a military processing unit in San Francisco to New York; there are photographs of Playboy Bunnies carrying the babies off the plane.

Some of the adoptees weren’t orphans at all, however, just children separated from their Vietnamese families, and the situation was fraught with cultural misunderstanding. There are stories of impoverished Vietnamese mothers effectively using orphanages as a place to keep their children safe, then returning weeks later to find they had been taken out of the country. As one later put it, “To understand my story, think you are caught upstairs in a burning house. To save your babies’ lives you drop them to people on the ground to catch. It’s good people that would catch them, but then you find a way to get out of the fire, too, and thank the people for catching your babies, and you try to take your babies with you. But the people say, oh no, these are our babies now, you can’t have them back.”

While Vietnam war adoptees mostly express immense gratitude for the lives they have had, there is also a sense of displacement, loss, and perhaps survivor’s guilt. “The first time I ever met adoptees it felt like group therapy,” says Rachel Gregg Galvez, an adoptee who grew up in the suburbs of New York and whose story features in Precious Cargo. She is co-founder of the South East Asian Coast to Coast Foundation, a non-profit company that helps reconnect families separated by the war. “Some of the adoptees I’ve worked with, on the surface they’ve had a great life but underneath they have this sadness and emptiness.”

Vietnam war adoptees also face a distinct and complex form of racial prejudice. A recurring theme in Precious Cargo is that Barton is continually judged by white people – from school friends to casting directors – as part of a group to which he feels little connection. Jennifer Adams, who was adopted by a family in Iowa, has a formative childhood memory of not being allowed to play at a white friend’s house because their father had served in the Vietnam war and didn’t want her there. Years later, as a teenager, she was selling snow cones at a community event when she saw the man again. “He came by and he very intentionally bought a snow cone from me, and I took it as his apology. He didn’t say I’m sorry and I didn’t need him to, I just needed to feel like he could acknowledge my existence.”

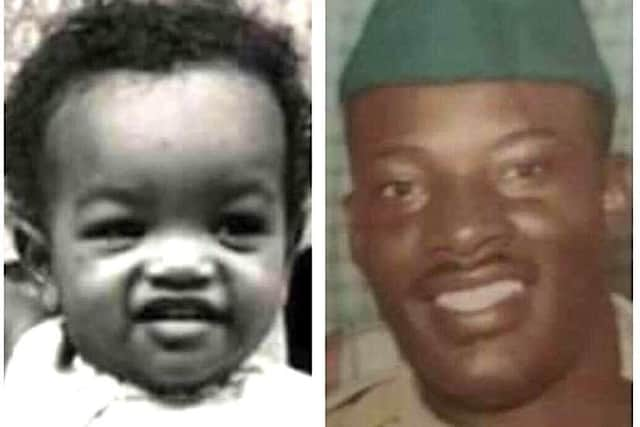

Toni Angelique Harrison, another adoptee whose story features in Precious Cargo, grew up as one of very few Black children in Biggleswade, a small town in Bedfordshire. Harrison says she didn’t understand that she was seen as a Black person until she was 15 or 16.

“As a teenager I didn’t like to talk about Vietnam,” she says. “I was only seen as Black, never Vietnamese.” She ended up internalising the racism in Hollywood movies about the Vietnam war. “In the films it was the African-American GIs who were shown killing Vietnamese people and raping Vietnamese women. It made me really angry at them. Racism is everywhere. It was only when I met some real GIs as an adult that I found out they were desperately looking for their Vietnamese families too.”

Harrison finally managed to find her biological father, an American ex-drill sergeant called Lee Butler, via a DNA search. Their emotional meeting was captured in a BBC news report in 2018; she also met other American relatives who had been previously aware of her existence but had no way to find her. It was the first time in her life, she says, that she’d been in a family photo with people who looked like her.

The increasing number of DNA tests, particularly in the USA, has resulted in a few reunions like this. Many Vietnam war adoptees were the product of relationships between American soldiers and Vietnamese women. Butler was with Harrison’s biological mother for two years, she discovered, but had to leave her behind when the army sent him back to the USA. Vietnamese parents are harder to track down, but Harrison remains determined to find her mother and hopes that sharing her story in an Edinburgh Fringe show will help with this.

“There are more success stories now, orphans finding fathers or siblings by using DNA companies like Ancestry or Family Finder,” she says. “But our biological Vietnamese mothers can’t afford to spend $100 on a DNA test. In Vietnam it could be a month’s wage. I set up a music festival called Free Spirit and we raised enough money to send 50 DNA kits to Vietnam. But time is not on our side. Our biological fathers and mothers are ageing or dying. The memories of the war are dying.”

Indeed, as Operation Babylift approaches its 50th anniversary and adoptees adjust to middle age and mortality, there is a strong sense of time running out. Williams’ beloved adopted mother died in autumn last year. His grief at her loss, he says, is part of the reason why he was so determined to tell this story now, a story that has become as much about looking for peace and acceptance as it is about continuing to search for lost relatives.

Like Yearley and Williams, Jennifer Adams returned to Vietnam as an adult a few years ago. She describes the experience as “life-changing” even though, like them, she found no trace of her birth family. But she wasn’t expecting answers, she says; she didn’t know her birth name or birth date and the orphanage she had been in no longer existed. She just wanted to see the “mother country” for herself. “Growing up, all I’d ever seen about Vietnam was through the lens of the US military, or Miss Saigon,” she explains. “I wanted to have a relationship that wasn’t through someone else’s lens or filter.”

Her description of her journey home is an eloquent summary of the Vietnam adoptee experience, the constant challenge of finding a place for yourself somewhere between different identities.

“When I came back from Vietnam after a month I remember coming in through LAX (Los Angeles International Airport) and there was a ginormous US flag and I started crying,” she recalls. “I’m not this overly patriotic person but seeing that flag represented to me ‘I’m home, I’m on firm ground again.’ That surprised me to be honest. I think this is probably a common experience for many transracial adoptees. I don’t get the advantage of having everything all in one. If I allow myself I could tell myself that I’m an outsider wherever I go. I was definitely an outsider in Iowa and in a way I was an outsider in Vietnam, they could take one look at me and know I wasn’t raised there. I’m just bigger, I have a different build. But I prefer to think of myself as an insider. In the US I find my commonalities, and I did the same in Vietnam.”

SCOTLAND: Precious Cargo is at An Lanntair, Stornoway, 6 July (www.lanntair.com), then Summerhall, Edinburgh, 1-26 August (www.summerhall.co.uk). Tickets for all performances are on sale now.